Dissonance to Informational Control in Technological Society: Part 5

Why governmental agencies make societal issues worse

Continued from Part 4…

This part looks at the nature of bureaucracy itself, arguing that it naturally seeks to expand the scope of the problems it seeks to solve (without solving them) in order to justify their expansion into larger organizations with more personnel, bigger budgets, and more power.

THE INCENTIVES FOR GOVERNMENTAL AGENCIES TO MAKE SOCIETAL PROBLEMS WORSE

If the country is falling apart at the seams, indoctrinated and sick, dying from a fentanyl epidemic, with open borders, a large and increasing wealth gap between rich and poor, high crime rates and the masses fooled by meta-narratives, unwilling to think Bad Thoughts because of the decrease in status associated with them and swayed by the deradicalization tools the government employs, can the government itself fix these problems, either by an elected president on a reform platform or from bureaucratic changes?

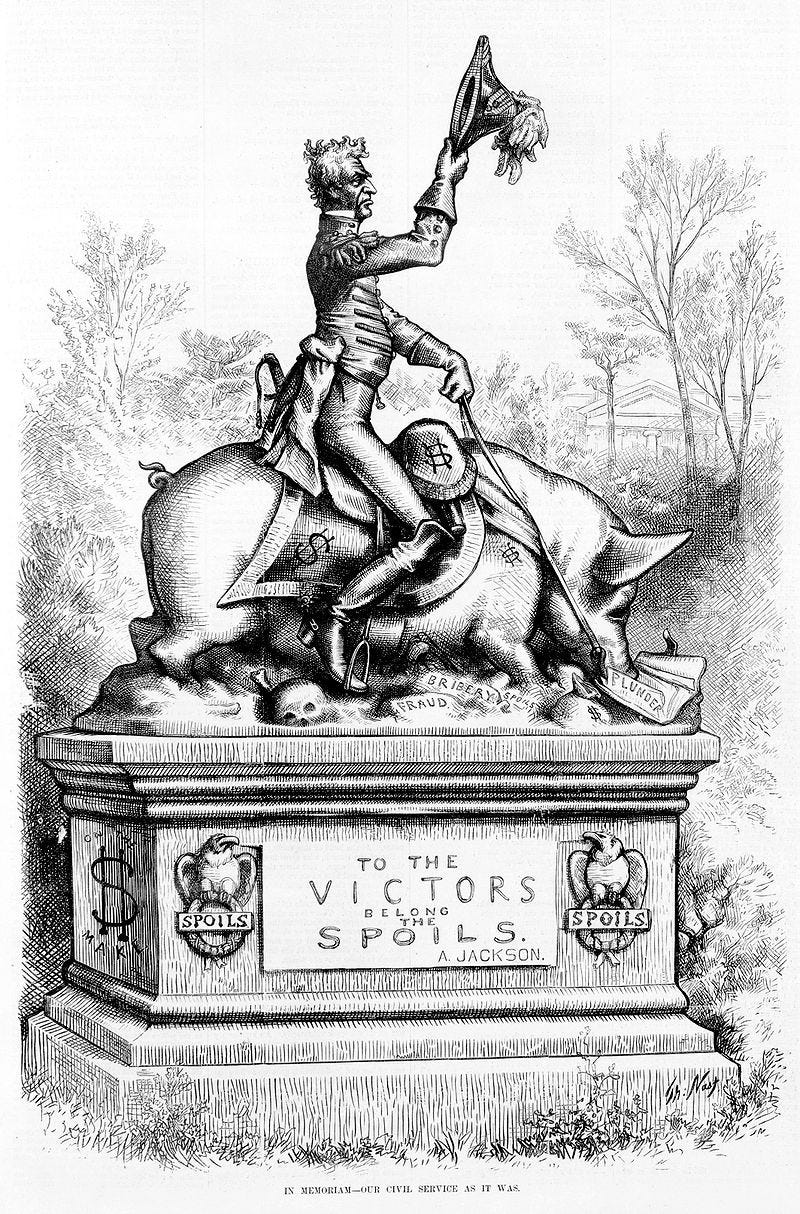

First, even if an elected leader wanted to institute significant reforms, it is close to impossible to fire entrenched federal civil service employees. This is because back in the 18th and 19th centuries most federal jobs were considered “patronage”, a perk that the party that won the presidential election could shower upon its supporters via the spoils system. However, this resulted in large turnover every election with government positions directed to loyal and well connected but unqualified individuals. Starting in the 1880s various acts were passed to establish federal jobs as “civil service” which would not be subject to elections or regular turnover, beginning with the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883. Over time more and more protections were added until it’s become extraordinarily difficult to fire anyone, making them immune to the popular will.

According to a report by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) only 77,000 full time federal employees were fired from 2000-2014:

“The 77,000 employees the MSPB says were fired over the past 15 years averages out to 5,133 employees annually, or just 0.26% of the 1,940,000 civil service workforce. But the percentage is even lower. MSPB [stated] that 41% of the fired employees were in their first-year, probationary period. These employees lack the extensive job protections of permanent federal employees. Adjusting to include only those employees past their probationary period, we arrive at a figure of just 0.15% of federal employees who are shown the door each year. Statistically, that is close to impossible.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics annual Job Openings and Labor Turnover survey, between 2005-2017 the private sector workforce maintained an average discharges and layoff rate of 17.27%, while the public sector maintained a rate of 3.37% over the same period, including terminations both for cause and general reductions in force. Once these figures are separated, it shows only 0.53% of federal employees were terminated for cause.

According to James Sherk at the Heritage Foundation, it’s much harder to fire government workers because of time-consuming and costly protections. "Federal law makes it very difficult to separate poorly performing federal employees from their jobs," Sherk says. "Managers who need to fire problematic employees, whether because of misconduct or poor performance, must go through draining and time-consuming procedures that take about a year and a half. Consequently, the federal government only rarely fires its employees, even when their performance or conduct justifies it," he said. "In fiscal year 2013 the federal government terminated the employment of just 0.3% of its tenured workforce for performance or misconduct."

Federal employees are also dramatically overpaid compared to the private sector as shown by federal government vs private sector average wages and average total compensation from 2000-2012.

An analysis by USA Today revealed particularly fast wage growth at the top end of the federal workforce. By 2009 there were 383,000 federal civilian workers with salaries greater than $100,000, 66,000 with salaries greater than $150,000, and 22,000 greater than $170,000. It has increased significantly since then.

These government workers are extremely sensitive to their salaries and positions within American society and they are hostile to any politicians or party that claims to want smaller government. Given this, is it any surprise that in the 2016 election Washington D.C. voted 90.86% for Hillary and 4.09% for Trump?

As the federal government employs 364,000 people in the D.C. area, not including contractors and other ancillary government jobs, one can conclude that the vast majority of federal workers voted for Hillary. When Trump won, many did everything they could to stymie his agenda from within their agencies without concern about being fired; see Peter Strzok, Lisa Page, Andy McCabe, John Brennan, James Comey as examples of civil service attempts to undermine elected officials. Indeed, these people bragged about it. Should an unelected civil service be able to override the policies goals of an elected president?

Worse than this, though, is the basic incentive structure for these organizations. For these bureaucracies, solving problems is actually the worst thing that they could do. This is because these organizations rely on government funding and they have to justify their budgets to the government on a yearly basis. For example, if the DEA solved the problem of drugs on the street what would happen to their funding? Their funding would get dramatically cut. This would be terrible for the careers of the people working there as well as for the organization itself and must be avoided. So how do you instead increase the size, prestige, and budget of your organization? The answer is simple: you create more problems to solve, not less (Parkinson’s law).

This is fundamentally why government is incapable of solving the problems it sets out to solve. This problem is summarized by Pournell’s iron law of bureaucracy, which states “In any bureaucracy, the people devoted to the benefit of the bureaucracy itself always get in control and those dedicated to the goals that [it] is supposed to accomplish have less and less influence, and sometimes are eliminated entirely.” This is summarized by Robert Conquest’s Third Law of Politics: “The simplest way to explain the behavior of any bureaucratic organization is to assume that it is controlled by a cabal of its enemies.”

Based on these incentives any sector the government involves itself in experiences a marked decline in quality and an enormous cost increase. Consider the price change for selected U.S. consumer goods and services compared to wages from 1997-2017:

Per the creator of this chart, “The greater the degree of government involvement in the provision of a good or service, the greater the price increases over time, e.g., hospital and medical costs, college tuition, childcare with both large degrees of government funding/regulation and large price increases vs. software, electronics, toys, cars and clothing with both relatively less government funding/regulation and falling prices.

As somebody on Twitter commented: Blue lines = prices subject to free market forces. Red lines = prices subject to regulatory capture by government. Food and drink is debatable either way. Conclusion: remind me why socialism is so great again.”

Basically, anything the government touches turns to hell.

Compounding these issues, governmental employees have developed a class consciousness over time. They belong to the same social circles; they speak the same vernacular; they deal with each other daily; their children go to the same schools. They see each other as part of the same class, and that outsiders — particularly middle America — pose a threat to their cushy jobs where they don’t have to work much, they can’t be fired, and they have extremely generous pensions. If middle America really knew the setup they would agitate to change it to the managerial class’s detriment, and that must be prevented. The label of “Republican” or “Democrat” is irrelevant here, it is about class: James Comey was desperate for Hillary to win despite being a registered Republican (the establishment joining together against the outsider Trump), and Trump’s Attorney General, William Barr, was close personal friends with witch-hunting Robert Mueller (also a registered “Republican”) and had ties to Jeffrey Epstein (Barr’s father gave Epstein his first teaching job). Barr also vigorously defended the sniper that killed Vicki Weaver, weaponless and holding a baby, at Ruby Ridge. There are a thousand examples of this.

It’s an incestuous environment and the unwritten rules require these government employees to defend each other regardless of transgressions. Even Andrew McCabe, caught redhanded lying to investigators regarding his leaking to media outlets and fired for cause, ultimately had his extremely generous pension reinstated and went on to write a book and receive generous media appearance fees. To the extent this managerial class identifies with other classes, it is with the globalist, jet-setting class of transnational elites, the Davos crowd, the oligarchical crowd. They make a show verbally of identifying with the lowest classes, illegal immigrants and various minority groups against white middle America — but it is a show, and they do everything they can to avoid seeing them within their own enclaves. For example, despite agitating for open borders, the D.C. mayor called in the national guard to remove busloads of illegal immigrants that Texas had sent over to them.

In his 1911 book Political Parties, German-born Italian sociologist Robert Michaels developed a political theory called the iron law of oligarchy to explain why this rising governmental class consciousness naturally arises from democracy and why it inevitably leads to oligarchy. Quoting from its Wiki:

"Any large organization, Michels pointed out, has to create a bureaucracy in order to maintain its efficiency as it becomes larger—many decisions have to be made daily that cannot be made by large numbers of disorganized people. For the organization to function effectively, centralization has to occur and power will end up in the hands of a few. Those few—the oligarchy—will use all means necessary to preserve and further increase their power.

According to Michels, this process is further compounded as delegation is necessary in any large organization, as thousands—sometimes hundreds of thousands—of members cannot make decisions via participatory democracy. This has to date been dictated by the lack of technological means for large numbers of people to meet and debate, and also by matters related to crowd psychology, as Michels argued that people feel a need to be led. Delegation, however, leads to specialization—to the development of knowledge bases, skills and resources among a leadership—which further alienates the leadership from the rank and file and entrenches the leadership in office. Michels also argued that for leaders in organizations, "The desire to dominate ... is universal. These are elementary psychological facts." Thus, they were prone to seek power and dominance.

Bureaucratization and specialization are the driving processes behind the iron law. They result in the rise of a group of professional administrators in a hierarchical organization, which in turn leads to the rationalization and routinization of authority and decision-making, a process described first and perhaps best by Max Weber, later by John Kenneth Galbraith, and to a lesser and more cynical extent by the Peter principle.

Bureaucracy by design leads to centralization of power by the leaders. Leaders also have control over sanctions and rewards. They tend to promote those who share their opinions, which inevitably leads to self-perpetuating oligarchy. People achieve leadership positions because they have above-average political skill (see Charismatic authority). As they advance in their careers, their power and prestige increases. Leaders control the information that flows down the channels of communication, censoring what they do not want the rank-and-file to know. Leaders will also dedicate significant resources to persuade the rank-and-file of the rightness of their views. This is compatible with most societies: people are taught to obey those in positions of authority. Therefore, the rank and file show little initiative, and wait for the leaders to exercise their judgment and issue directives to follow."

Michaels became a fascist supporter of Mussolini in Italy as a result of his observations.

The other problem of bureaucratization is it saps the energy and motivation of the general population by depriving them of the ability to influence political decision-making. In the foreword to the George Schwab translation of Carl Schimtt’s Political Theology, Tracy B. Strong argues:

"When Max Weber described the workings of bureaucracy he asserted that in no case are bureaucratic (rationalized, rational-legal) relations, relations between human persons, between human beings. Bureaucracy is the form of social organization that rests on norms and rules and not on persons. It is thus a form of rule in which there is “'objective’ discharge of business according to calculable rules and 'without regard for persons. What he meant is that it was in the nature of modern civilization to remove the non-rational from societal processes, replacing it by the formalism of abstract procedures. (He did not think everything was always already like this—merely that this was the tendency.) The disenchantment of the world is for Weber the disappearance of politics, hence the disappearance of the human, hence the lessening of the role that the non-rational and non-rule-governed play in the affairs of society. “Bureaucracy,” he will proclaim, “has nothing to do with politics.”

This is Schmitt’s theme also. “Today nothing is more modern than the onslaught against the political….There must no longer be political problems, only organizational-technical and economic-sociological ones” (PT, 65)….[If] the political is in danger of disappearing as a human form of life, this can only be because sovereignty as Schmitt understands it is increasingly not a constituent part of our present world. Thus in his book on Hobbes, he will write ‘the mechanization of the conception of the State has ended by bringing about the mechanization of the anthropological understanding of human beings.’”

****

We have established that the quality of life for Westerners has been rapidly declining, that bureaucratic institutions make problems worse and that the establishment has many tools to prevent the population from effectuating change. The next question is why is this happening? Are there natural processes involved or are there deliberate actors with specific goals? Before presenting a comprehensive theory in Section 4, let us review other possible explanations in Part 6, the final part of “Dissonance to Informational Control in Modern Society”.

Having recently discovered this Substack I find myself following the links in any one article back and then back again. This is a goldmine of great information. Fantastic work!

“The disenchantment of the world is for Weber the disappearance of politics, hence the disappearance of the human, hence the lessening of the role that the non-rational and non-rule-governed play in the affairs of society. “Bureaucracy,” he will proclaim, “has nothing to do with politics.”

How is the term politics being used here? It doesn’t seem to be in the context I’m used to seeing it.

It doesn't fit the dictionary definition of group decision making. It seems to refer more to a meta-physical, ethical, moral framework used to guide decision making -- or here I read it as the replacement of said framework by a "rational" framework.

Logic, and reason alone necessary but insufficient tools for humane decision making. A moral or ethical framework is required - perhaps that is the point being made?